5 Language Mysteries No One’s Been Able to Solve

It’s a good thing you have the power of language because that’s how you know nearly everything you know. You’ve experienced some stuff yourself, but everything else in your mind comes from words you’ve heard or read.

Imagine if words didn’t mean what you think they do. You read a news report about some victim being murdered by a succubus, but what if a succubus isn’t really a demon? What if it’s some special type of Golden Retriever? With some old words, especially those that have been clumsily translated, we’re just taking shots in the dark.

What Does ‘Our Daily Bread’ Mean Anyway?

One story from the Bible tells of the time Jesus taught his followers how to pray. When you pray, said Jesus, you shouldn’t just go on repeating some set words. That’s what pagans do. Plus, God knows what you need, so you don’t have to ask. Instead, said Jesus, try talking like this. And he prayed aloud, just freestyling.

Don't Miss

His followers wrote down the words he said and repeated them verbatim for the next 2,000 years. They taught the prayer to their children, who would learn to recite it long before they had any idea what such phrases as “thy will be done” mean. This is the opposite of what Jesus told them to do, but that’s organized religion for you.

That prayer is called the “Our Father” or “The Lord’s Prayer.” Though, people today don’t use the exact words that were said millennia ago, because not too many people speak Aramaic anymore. Even if you do speak Aramaic, that 2,000-year-old transcription went through translation, and all current translations stem from one version of the prayer recorded in Greek. Here’s where deciphering the prayer’s meaning gets complicated.

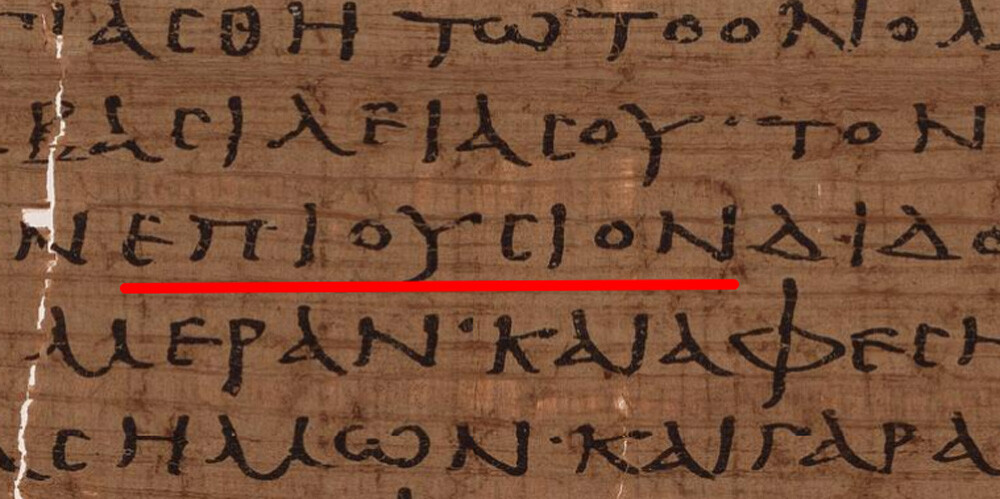

“Give us this day our daily bread,” says one line of the prayer, as people know it today. In Greek — found on a New Testament papyrus dating back to the year A.D. 200 — that’s “Τὸν ἄρτον ἡμῶν τὸν ἐπιούσιον δὸς ἡμῖν σήμερον.” The word “ἐπιούσιον” there (let’s call it “epiousion” for convenience) is the word “daily” in that line. But we’ve never seen epiousion in any context other than this prayer. We don’t know it means “daily.” We just have to guess its meaning.

Translators said it means “daily” because the first part of the line says “give us this day,” or “give us today.” That makes sense, from a certain point-of-view. From another point-of-view, it makes no sense. If we’re already talking about what we’re going to receive this day, calling the bread “daily” is redundant. “Daily” would therefore be the one word epiousion can’t mean.

Don’t bother asking the Pope for guidance on this one. Even the Vatican says multiple meanings are possible. So, maybe the prayer originally asked, “Give us this day our sliced bread.” Sliced bread did not exist back then, but with God, all things are possible. Or maybe it said, “Give us this day our garlic bread.” That’s a prayer to unite people of all faiths.

One Mystery Verse of Dante’s ‘Inferno’

Education means different things in different eras. Today, to be a properly educated scholar of culture, you need to be able to explain where every Disney remake went wrong, even though you have never watched any of them and rightly never intend to. In the past, in certain circles, an educated person was someone who’d studied Greek and Latin. You did not know much chemistry or how to milk a cow, but you knew how to translate Homer, Horace and Herodotus.

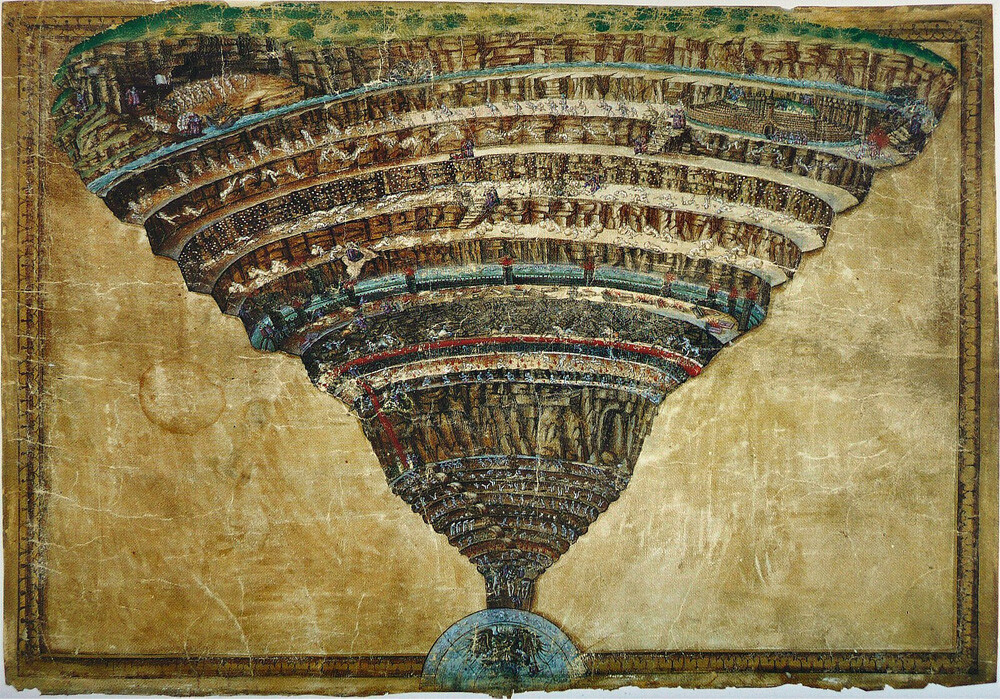

Perhaps you would have to translate the ancient works of Virgil, which sounds hard. Much easier, surely, would be translating a poem written 1,300 years after Virgil, featuring Virgil as a character. The poem’s called the Divine Comedy and was written in Italian, hardly as dead a language as Latin. But then you’d come upon a verse that goes like this: Raphèl mai amècche zabì almi. What does that mean?

We don’t know. It’s not Italian. Nor is it any other language we know of. The character who says it is Nimrod, a hunter from the Bible guarding the ninth circle of hell, and it seems like this line of his may be gibberish. Once the Tower of Babel fell, people started speaking different languages, and this unintelligible line may reference that. On the other hand, Dante didn’t just mash a bunch of keys to produce this sentence. It looks like it takes inspiration from multiple languages, so the words may mean something after all.

Some see in this line Old Hungarian, which might make sense, considering Dante had Hungarian friends. Tweak the words a bit, and they turn into the Hungarian words Rabhely majd, amelyek szabja állni, which translate as “It’s a jail that forces you to stay here.” Or maybe we’d have more luck looking at the biblical Hebrew and Chaldean languages. Try that, and you can spin the words as Refa el mai amech zebai almi, which translates as “C’mon, God! Why annihilate my army in this world?”

To find out for sure, we’d have to journey into the underworld and consult Dante. This just raises further issues, however. For starters, when we’re down there, who will guide us?

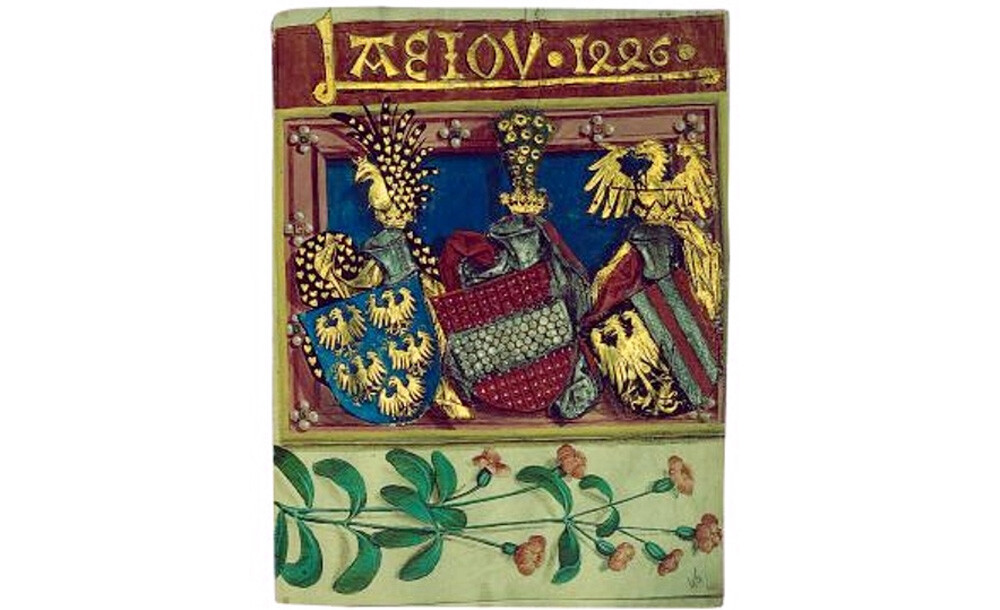

The Vowel Vow of the Royal Habsburgs

The Hapsburgs, starting with King Frederick III in the 15th century, used the following motto: “A.E.I.O.U.” Those are, of course, the five vowels of the alphabet. You’ll see the letters in the personal writings of royals, carved into buildings and painted onto various valuable old doodads from the period.

via Wiki Commons

Throwing the motto into Google tells us what they stood for. They stood for Alles Erdreich ist Österreich untertan, which means “All the world is subject to Austria.” Cool, cool. Question answered.

However, a deeper mystery runs here. That interpretation of the words comes from a notebook of Frederick himself, but this annotation that supposedly offers the meaning appears to be written by someone other than him. For all we know, that writer could have been a fellow adventurer who discovered the notebook and was trying to decode its clues, in search of treasure. Further in the same notebook, we see a line from a poem: Amor electis, iniustis ordinor ultor. That's A.E.I.O.U again, surely not a coincidence. But that translates to something totally different, translates as “I am loved by the elect; for the unjust I am ordained an avenger.”

One volume from the year 1600 says the letters stood for Aquila electa iusta omnia vinci, or “The chosen eagle just won everything.” Another phrase popped up in some old books from this region: Austria erit in orbe ultima. That translates as “Austria will be supreme in the world.” Let’s be sure to keep an eye on any man born in Austria. Some of them seem to harbor sinister ambitions.

Who the Devil Is Betsy?

“Heavens to Betsy!” says the old exclamation. It’s a way of expressing shock. Descriptions of this idiom liken it to “for heaven’s sake,” a phrase that began as a euphemism, because the preferred earlier phrase, “for Christ’s sake,” was considered sacrilegious.

Fine, that's what “Heavens to Betsy” expresses. But what do the words literally mean? Like, are they saying heaven is going to Betsy, or are they comparing heavens to Betsy? And here’s the real question we want answered: Just who is Betsy, anyway?

Some sources speculate that it’s Betsy Ross, since popular myth gives her such a revered place in American culture. But we see the phrase dating back as far as 1857, which was before Ross was (falsely) first credited with stitching the American flag.

For comparison, we know who Pete is in “For Pete’s sake.” It’s Saint Peter. We know who Jove is in “By Jove.” It’s the Roman god Jupiter (this was another oath considered less blasphemous than citing the Christian God). But Betsy? Betsy is a mystery. All we know is she’s surely immortal and is probably reading this article at this very moment.

Is Copacetic a Word at All?

Copacetic means “all right.” You’ll most often hear it when someone’s being verbose for the sake of comedy (don’t scoff — comedy comes in many forms). We can trace the history of this word to a single book from 1919, a piece of historical fiction featuring Abraham Lincoln as a character. In that sense, “copacetic” is less mysterious than most words you encounter every day. When we dig into that book, though, things get weird.

20th Century Studios

The book was A Man for the Ages by Irving Bacheller. A woman there describes one man’s appearance as “copasetic.” This man is not Lincoln; Lincoln was not known for his good looks. It’s the husband of one woman in the scene, a guy “stout as a buffalo.” From context, they’re calling him strong, not fat, so you can come away from this passage knowing that copasetic means some variation of “fine.” At another point in the book, someone else uses the word, and they do so quoting the woman from before. “In the words of Mrs. Lukins, ‘It is very copasetic’,” says a soldier being offered lodgings.

The word appears a third time in the book as well. Here, the book begins by saying that this Mrs. Lukins would sometimes use a word called “coralapus” — a word which does not exist. We can find no reference to it anywhere but this book, and the book says that it has an “indefinite meaning.” Then, the book says, “There was one other word in her lexicon, which was in the nature of a jewel to be used only on special occasions. It was the word ‘copasetic.’ The best society of Salem Hill understood perfectly that it signified an unusual depth of meaning.”

Copasetic spread from this book, and that’s not so strange. All words have to start somewhere. Shakespeare is credited with inventing hundreds of words (he didn’t invent all of those, but he probably invented some of them). The word also mutated a bit in spelling, from copasetic to copacetic. That’s not so strange either.

Here’s the strange part: It’s unclear whether the original author, Irving Bacheller, intended for it to be a word at all. Rather than coining a word for the sake of expressing an idea, he may have created a word as a joke, where the fact that the word wasn’t a real word was the whole joke.

No one treats it as a joke now. So, have we all been fooled by a word that’s the equivalent of — and indeed has the same meaning as — cromulent?

Follow Ryan Menezes on Twitter for more stuff no one should see.